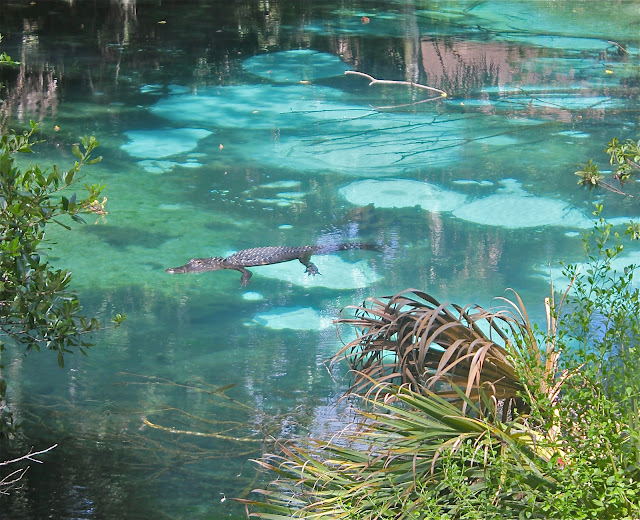

A toxic strain of blue-green algae may be involved in the skyrocketing number of alligator deaths in Lake Griffin over the past two years, state officials and University of Florida researchers say.

Cylindrospermopsis, which accounts for up to 90 percent of the microscopic floating algae in the lake, is the likely culprit because it produces toxins known to cause death in animals, UF researchers and the UF Conservation Commission recently discovered. Florida Wildlife and Fisheries.

Experts have been stumped by the dramatic change in the lake, where they say two or three alligator deaths a year would be normal, not the more than 200 in the past two years.

“The types of toxins normally associated with cylindrospermopsis algae have been hepatotoxins, which affect the liver and kidneys.

but in alligator deaths, there has been no indication of hepatotoxin action,” said Edward Phlips, associate professor at the UF Institute of Agricultural and Food Sciences.

“However, a new study by Chilean researchers indicates that some forms of cylindrospermopsis produce a neurotoxin that would not contradict the alligator deaths that occur in the lake.”

The results of the study, which analyzed water in and around Sau Paulo, Brazil, were published in the October issue of the journal Toxicon.

Phlips said there have been no reports of human deaths associated with cylindrospermopsis blooms.

Perran Ross, a conservation biologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History at UF, and other researchers have been at a loss to explain the alligator die-off.

“It’s a mystery why they’re dying and it’s a little disturbing that something as big and hardy as an alligator is being affected by something in this lake,” Ross said.

Initial examinations of the alligators revealed nothing unusual, Ross said. The alligators did not exhibit the more serious problems generally associated with any of the known cylindrospermopsis toxins, he said.

“After a very extensive examination, we were disappointed to find very few problems with them,” Ross said. “All of its internal organs and systems appeared to be normal, and its blood values were similar to those reported for other alligators.”

But more precise tests by Trenton Schoeb, a professor of pathobiology at the UF College of Veterinary Medicine, revealed other problems with the giant reptiles.

“The alligators were found to have neural deficiencies,” Ross said. “Their nerve conduction speed is about half that of normal alligators. “Many of them have microscopic signs of peripheral nerve damage and have lesions in the brain.”

Phlips said it’s difficult to establish exactly how long the algae has been in Florida, but it has become a major feature of Lake Griffin’s plankton community for more than five years.

In recent years, algae has become an unwelcome and uncomfortably abundant guest in the 9,000-acre lake.

“The situation is that there are a lot of cylindrospermopsis in Lake Griffin now,” Phlips said. “It is very dense and persists for much of the year.

“Lake Griffin is one of the lakes most likely to bloom in Florida in recent years. “We have been sampling for the past five years and cylindrospermopsis has been flowering for that entire period,” he said.

But whether or not cylindrospermopsis is the cause of the alligators’ deaths, Ross said, the abundance of algae is a symptom of a general problem with Lake Griffin that has no easy solution.

“The algae may be producing the toxin that is affecting the alligators, but it is certainly affecting the ecology of the lake,” Ross said.

“There are almost no bass in this lake anymore, but there are plenty of catfish and other less desirable species that do well in this muddy, murky, highly nourished water. “Toxic algae and dead alligators are symptoms of a widespread disturbance in the lake’s ecology.”