In 1991, two German hikers made a remarkable discovery in the Eastern Alps—a perfectly preserved frozen corpse dating back over five millennia. This 5,300-year-old mummy, famously known as “Iceman” or “Ötzi,” has become a treasure trove for paleomicrobiologists, offering insights into the diet and lifestyle of Copper Age humans.

In a collaborative effort spanning the globe, scientists have successfully isolated and mapped the genome of a bacterium residing in Ötzi’s stomach, identified as Helicobacter pylori. This bacterium is a common inhabitant of the modern human gut. However, the unique strain found in the Iceman has opened a window into previously mysterious human migration patterns. The research also suggests a potential addition to the myriad health challenges faced by this ancient mummy, adding another layer to the enigma surrounding everyone’s favorite frozen relic.

Due to a handful of key characteristics, such as a high mutation rate, H. pylori bacteria serve as a valuable marker for tracing the history of human dispersal and migration. The presence of this bacterium in the ancient stomach of the Iceman has captured the attention of evolutionary biologists from Austria, Italy, South Africa, Germany, and beyond.

Yoshan Moodley, a researcher at the University of Venda in South Africa and an author on the new Iceman paper, stated, “It provides almost literally a mirror image of human population structure.”

Through the application of DNA-amplification techniques, meta-genomic diagnostics, and targeted genome capture, scientists have identified the H. pylori in the Iceman as a specific Asian strain. Notably, only three such strains have ever been detected in modern Europeans. The Iceman’s H. pylori represents the first evidence that this particular strain was already present in Central Europe during the Copper Age, roughly between the 5th and 3rd millennia BC. This revelation sheds new light on ancient human migration patterns and challenges previous assumptions about the geographic distribution of specific bacterial strains in ancient populations.

Because the strain of H. pylori found in the Iceman is more closely related to Asian strains than the various Asian-African hybrids observed today, this discovery suggests that the mixing of Asian and African strains had not yet occurred during the Iceman’s lifetime.

Yoshan Moodley remarked, “We can now say that the waves of migration bringing African H. pylori into Europe had not occurred in earnest by the time the Iceman was around.”

While approximately 10% of current H. pylori carriers develop ulcers, it appears that the Iceman might have been among the unfortunate few. Although researchers cannot definitively determine whether he experienced stomach pain, it likely wasn’t the most severe of his health challenges.

“He had a rough lifestyle,” Moodley noted. “He was walking extensively in the mountains, suffered from degenerative diseases in his lower back and knee, had intestinal parasites, and Lyme Disease.”

Shockingly, none of these health issues contributed to his ultimate demise; he met his end from an arrowhead unleashed by an unknown assailant. The Iceman’s medical history provides a captivating glimpse into the challenges faced by ancient individuals, highlighting the complexities of health and survival in a bygone era.

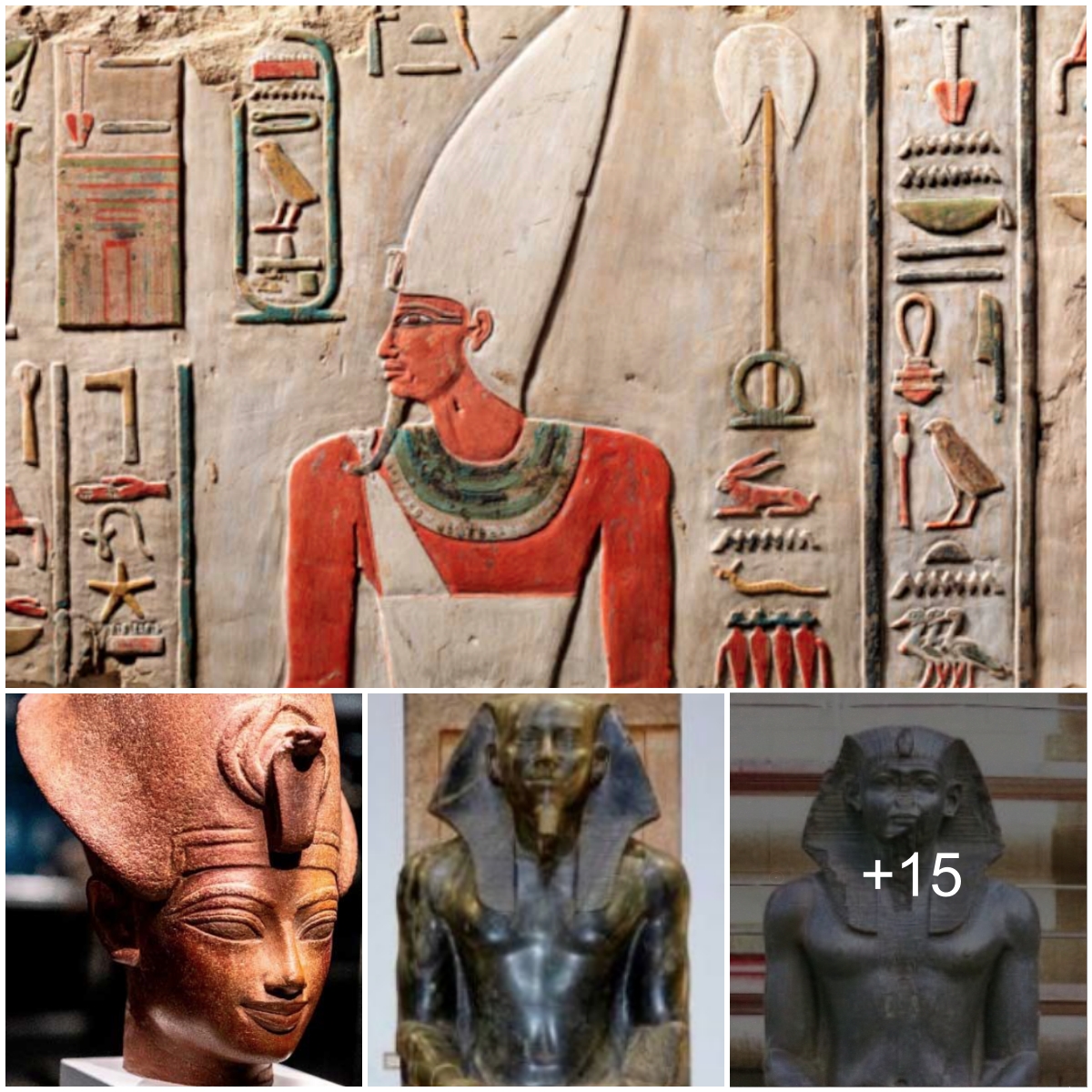

While the bacteria found in the Iceman’s gut offer just a singular sample, scientists are eager to connect the dots by comparing this research with findings from other mummies around the world—except, unfortunately, ancient Egyptian mummies, as their stomachs were typically removed during the mummification process.

“I think that Ötzi’s benefit to all of us is that we keep pushing back frontiers of human activity,” emphasized Patrick Hunt, an archaeological scientist at Stanford.

Hunt and other researchers anticipate that the Iceman will remain a valuable gift to science, providing ongoing insights.

“It’s highly improbable that there will ever be another Ötzi—the circumstances of the way he was discovered and preserved are very extraordinary,” remarked James Dickson, a professor of archaeobotany and plant systematics at the University of Glasgow. “If you think back 100 years—there was no radiocarbon dating, and so on and so forth. If we project 100 years into the future, what on earth will we have found out?” The Iceman’s unique circumstances and the advancements in scientific methods make him an irreplaceable source of information, continually pushing the boundaries of our understanding of ancient human history.