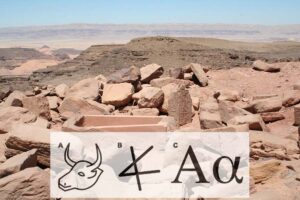

As incredulous as it may seem, historical evidence firmly establishes that the letter “A” had its origins in the Egyptian hieroglyph representing an ox. However, its truly remarkable transformation occurred when miners working in the turquoise mines of ancient Egypt appropriated this hieroglyph, transforming it into graffiti. This seemingly minor adaptation played a pivotal role in the development of syllabic alphabets, including the widely used Latin alphabet seen worldwide today.

The narrative unfolds nearly 4,000 years ago in Egypt when the turquoise mines of the Sinai Peninsula became pivotal on an industrial scale. Individuals from various strata of Egypt’s Bronze Age society engaged in mining activities at the mountainous Serâbît el-Khâdim, the location that now holds historical significance. The Sinai Peninsula, with its numerous mining sites for various raw materials, emerged as a central quarrying hub during this era.

From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to the Latin Alphabet

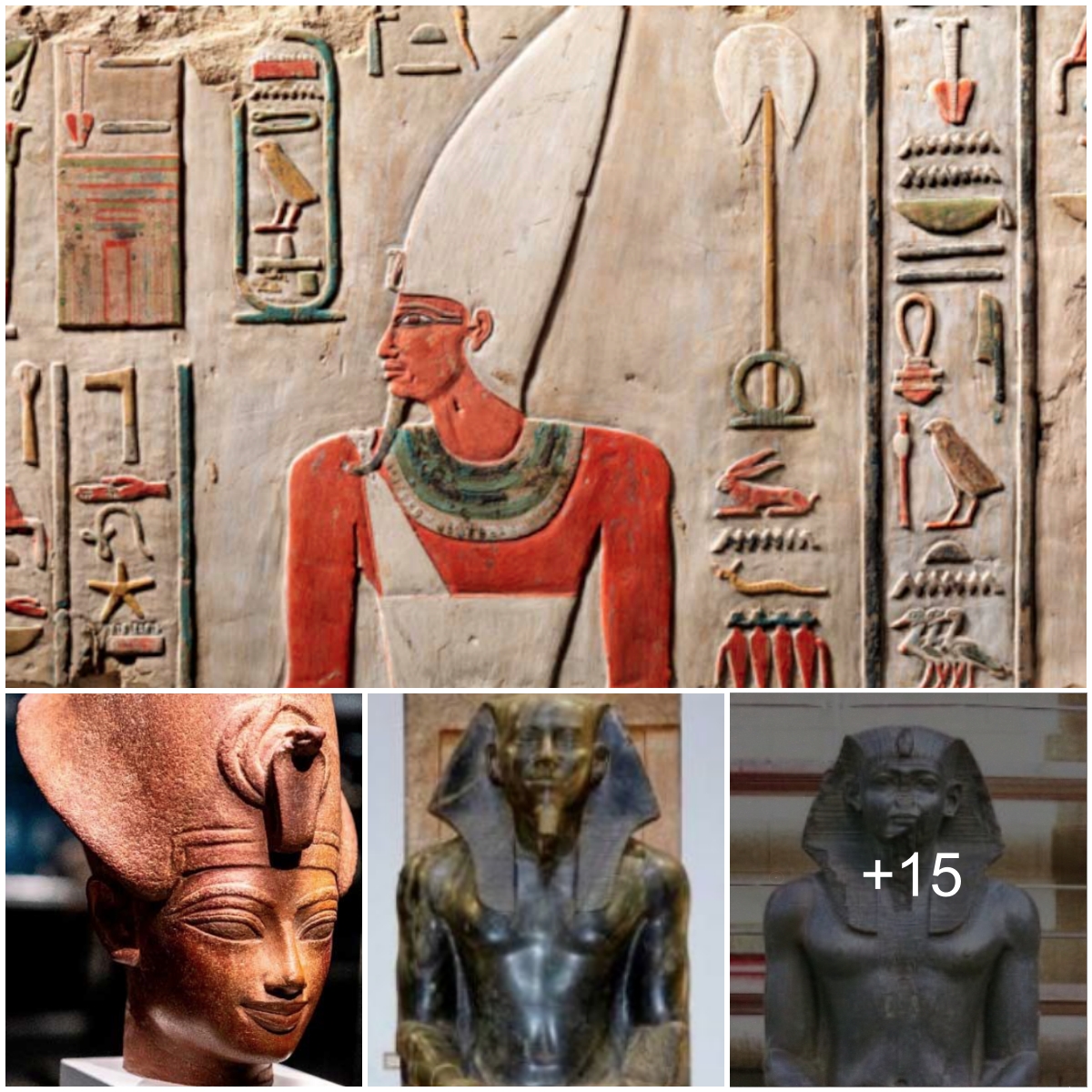

During the era around 1900 BC, the Egyptian language relied on hieroglyphs for written expression. Primarily logographic, these hieroglyphs assigned meanings to individual symbols rather than phonetic sounds. With thousands of intricate hieroglyphs in existence, acquiring the expertise to learn, memorize, and write them became a specialized skill.

Similarly, the Bronze Age Mesopotamians employed cuneiform pictographs on clay tablets to transcribe their Sumerian language. In both Egypt and Mesopotamia, written language served diverse purposes, ranging from religious dedications to mundane records of produce and land ownership, reflecting both sacred and secular aspects of society.

Despite the widespread utilization of these early writing systems, their inherent complexity persisted. The transformative breakthrough came with the invention of the alphabetic system, revolutionizing literacy by simplifying the entire process of reading and writing.

Temple of Hathor in Serâbît el-Khâdim in Egypt. (Felipe Ligeiro FL / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Graffiti That Revolutionized Literacy: The Temple of Hathor in Serâbît el-Khâdim

In the vicinity of the Serâbît el-Khâdim mines, situated in the southwestern Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, a temple dedicated to Hathor stood for 800 years, providing spiritual solace to those engaged in mining activities. Undergoing multiple phases of reconstruction, the temple held a central significance in the lives of individuals who either spent time or traversed this arid landscape.

Comprising a grand sanctuary with a processional avenue, various buildings, rooms, and numerous stelae adorned with hieroglyphic inscriptions, the temple served as a place of devotion for priests, miners, officials, interpreters, scribes, and others. Hathor, revered as the “mistress of turquoise” among her other epithets, was the focal deity of this sacred site.

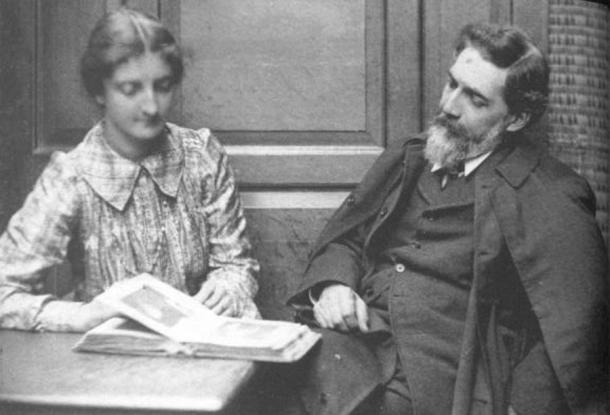

The Serâbît el-Khâdim site was initially uncovered in 1762, and over the subsequent century, antiquarians explored the area, particularly after the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs in 1822. In 1905, during an expedition to the deserted mines and the temple, two Egyptologists, the married couple William and Hilda Flinders Petrie, stumbled upon an extraordinary find. They observed graffiti in and around the mines, exhibiting a script distinct from the Egyptian hieroglyphs prevalent across the site.

During their visit, the Petries meticulously documented, mapped, and photographed fourteen turquoise mines, circular enclosures near the temple, and the temple itself. The inscriptions revealed references to various pharaohs, indicating the prolonged usage of the area. Additionally, tools, altars, figurines, amulets, pottery, seals, and jewelry provided insights into the daily life and practices associated with the site.

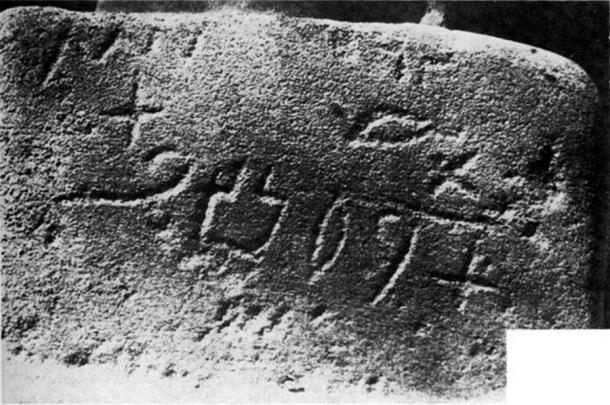

The peculiar graffiti symbols were discovered on fallen stones near the mines and several statues within the temple grounds. In contrast to the formal stelae adorned with finely carved hieroglyphs leading to the temple, these symbols were less numerous. Despite the limited etchings, Petrie analyzed them and became convinced that they had unearthed the earliest evidence of an alphabetic system.

The Irish-born British Egyptologist Hilda Petrie and her husband the British Egyptologist Flinders Petrie were the first to notice the graffiti markings at Serâbît el-Khâdim. (Public domain)

Ancient Graffiti as Earliest Evidence of an Alphabetic System

The breakthrough in deciphering the graffiti came in 1916 when fellow Egyptologist Alan Gardiner successfully translated the inscriptions. He identified the repeated use of certain characters, which he phonetically interpreted to spell out the word “Baalat.” In Canaanite, this term signified “the mistress,” a designation Gardiner equated with the Egyptian goddess Hathor.

The pivotal moment in unraveling these inscriptions occurred when Gardiner examined bilingual engravings on a small sphinx figurine discovered in the temple. On one side, an inscription in Egyptian hieroglyphs read “the beloved of Hathor,” while the other side featured an inscription in the mysterious graffiti reading “the beloved of Baalat.”

This discovery proved analogous to the Rosetta Stone, surpassing the translation of a second language. It demonstrated that the second language was expressed through an adaptation of Egyptian hieroglyphs and was employed syllabically. Petrie’s intuition was validated—this marked a simplified version of Egyptian hieroglyphs where each character represented a sound rather than an entire word. It emerged as the earliest-known syllabic script, celebrated as a potential precursor to alphabetic systems.

Termed Proto-Sinaitic by experts, this script would later evolve and disseminate through trade, with significant contributions from the Phoenicians. However, the identity of the individuals responsible for the graffiti and the precise timing of its creation remain subjects of debate. The consensus suggests that the graffiti likely originated during the reign of Amenemhet III in the middle Bronze Age. It is believed to have been crafted by Asiatic people, possibly of Canaanite origin, as indicated by the inscriptions featuring Baalat.

Stelae adorned with hieroglyphic dedications by interpreters further imply that individuals speaking different languages participated in expeditions to the mines. During this period in Egypt, many Asiatic people resided in the eastern delta region, with records documenting discussions among Egyptians about their mixed parentage. It is plausible that these diverse groups were part of the recorded expeditions to the mines.

A Serabit inscription found by Flinders Petrie at Serâbît el-Khâdim which spell out the name of the goddess Baalat. (Public domain)

Semi-Literate Origins of a Revolutionary Concept

The educational background of the individuals responsible for the graffiti remains a subject of debate. Some argue that these inscriptions were likely created by semi-literate individuals with limited proficiency in Egyptian hieroglyphs. According to this perspective, they devised this abstract version to convey messages in their own language. The primitive and inconsistent forms of these early letters, scattered across random rocks, support this theory.

However, there are experts who propose an alternative view, suggesting that these workers were skilled and educated. If alphabet creation indeed resulted from the ingenuity of barely literate mine workers for personal use, it represents a remarkable accident in history, profoundly altering the way language is written and read across various countries and cultures.

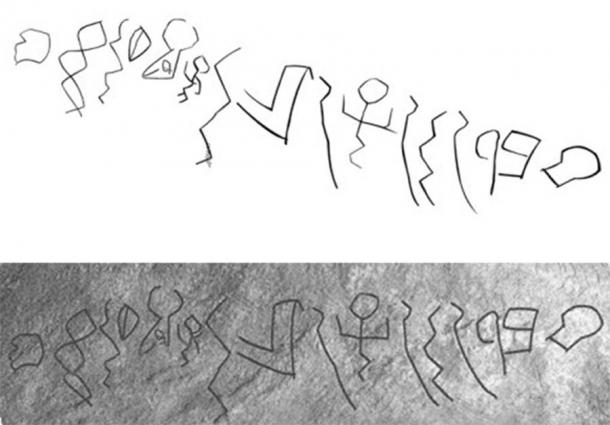

In 1993, similar inscriptions resembling those at Serâbît were uncovered in Wadi el-Hôl near Luxor. These inscriptions, etched into limestone rocks, featured two lines in the valley. Initially thought to be older than those at Serâbît, experts now believe they came later. It is plausible that miners familiar with the script from Serâbît traveled to Wadi el-Hôl.

The graffiti underwent multiple transformations over an extended period before serving as the foundation for numerous alphabets used today. The exact timeline and mechanisms behind the dissemination of these symbols beyond the Sinai Peninsula, ultimately shaping the future of literacy, remain unclear. However, it is evident that this process spanned many years.

Wadi el-Hol inscription with tracing above and photograph below. (Public domain / Public domain)

The Evolution of Egyptian Hieroglyphs into the Latin Alphabet

It’s captivating to observe the evolution of specific Egyptian hieroglyphs through the Proto-Sinaitic script, eventually giving rise to the Latin letters in use today. For instance, the letter “B” traces its origins to the Egyptian hieroglyph representing a house. The letter “H” had its beginnings as the Egyptian hieroglyph for a fence, while the letter “K” emerged from the Egyptian hieroglyph denoting a hand. These early symbols served as the foundation for the Proto-Sinaitic, Ugaritic, Phoenician, and Greek alphabets, each introducing its modifications to the original forms.

It’s intriguing to note that the early alphabets were abjads, featuring only consonants. In the Phoenician version, their adaptation of the Egyptian hieroglyph for an ox represented a glottal stop, a feature that posed challenges for the Greeks as they adopted the alphabet. Consequently, the Phoenician letter “aleph” underwent transformation into the Greek letter “alpha,” representing the vowel sound “a.”

For those delving into historical analysis, the significance of written language cannot be overstated. Texts and inscriptions provide invaluable insights into historical periods, especially those preceding the Neolithic era. Without the introduction of the syllabic alphabet, the availability of textual evidence from the past few millennia might have been even scarcer.

While other factors such as the development of paper, advancements in education, and the invention of the printing press played crucial roles, the syllabic alphabet distinctly contributed to the recording and transmission of information from the end of the Bronze Age onward.

The complexities of the origins and evolution of alphabetic systems, including the Latin alphabet, are acknowledged, and this discussion offers a simplified overview. It underscores the idea that many impactful inventions often originate as serendipitous events in history. The development of spoken languages, like written languages, involves intricate stories intricately linked to a multitude of influencing factors.

The provided images depict the deciphering of potential origins of the Latin alphabet in graffiti discovered at the Temple of Hathor near the Serâbît el-Khâdim mines. The evolution of the letter “A” is highlighted in the foreground, emphasizing the historical significance of these findings.

References

1. **Colless, B.E. (2014). The Origin of the Alphabet: An Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis. Antiguo Oriente: cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente, (12), pp.71-104.** This paper, authored by B.E. Colless in 2014, critically examines the Goldwasser Hypothesis regarding the origin of the alphabet. The Goldwasser Hypothesis likely proposes a theory or model related to the development of the alphabet.

2. **Gardiner, A.H. (1916). The Egyptian origin of the Semitic alphabet. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 3(1), pp.1-16.** A work by A.H. Gardiner from 1916, this article explores the connection between the Semitic alphabet and its Egyptian origins. Gardiner may discuss historical and linguistic evidence supporting the Egyptian influence on the development of the Semitic alphabet.

3. **Goldwasser, O. (2010). How the Alphabet was Born from Hieroglyphs. Biblical Archaeology Review, 36/2 pp. 40-53.** Authored by O. Goldwasser in 2010, this article published in the Biblical Archaeology Review discusses the process through which the alphabet emerged from hieroglyphs. Goldwasser likely presents evidence and arguments supporting the idea that the alphabet had its roots in hieroglyphic writing systems.

4. **Mumford, G. (2015). The Sinai Peninsula and its environs: Our changing perceptions of a pivotal land bridge between Egypt, the Levant, and Arabia. ASAA Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 7(1), pp. 1-24.** In this 2015 publication by G. Mumford, the focus is on the Sinai Peninsula and its role as a land bridge connecting Egypt, the Levant, and Arabia. The article likely explores archaeological and historical perspectives on the significance of the Sinai Peninsula in ancient times.

These references contribute valuable insights into the historical, linguistic, and archaeological aspects of the development and transmission of the alphabet, particularly in relation to Egyptian influences.